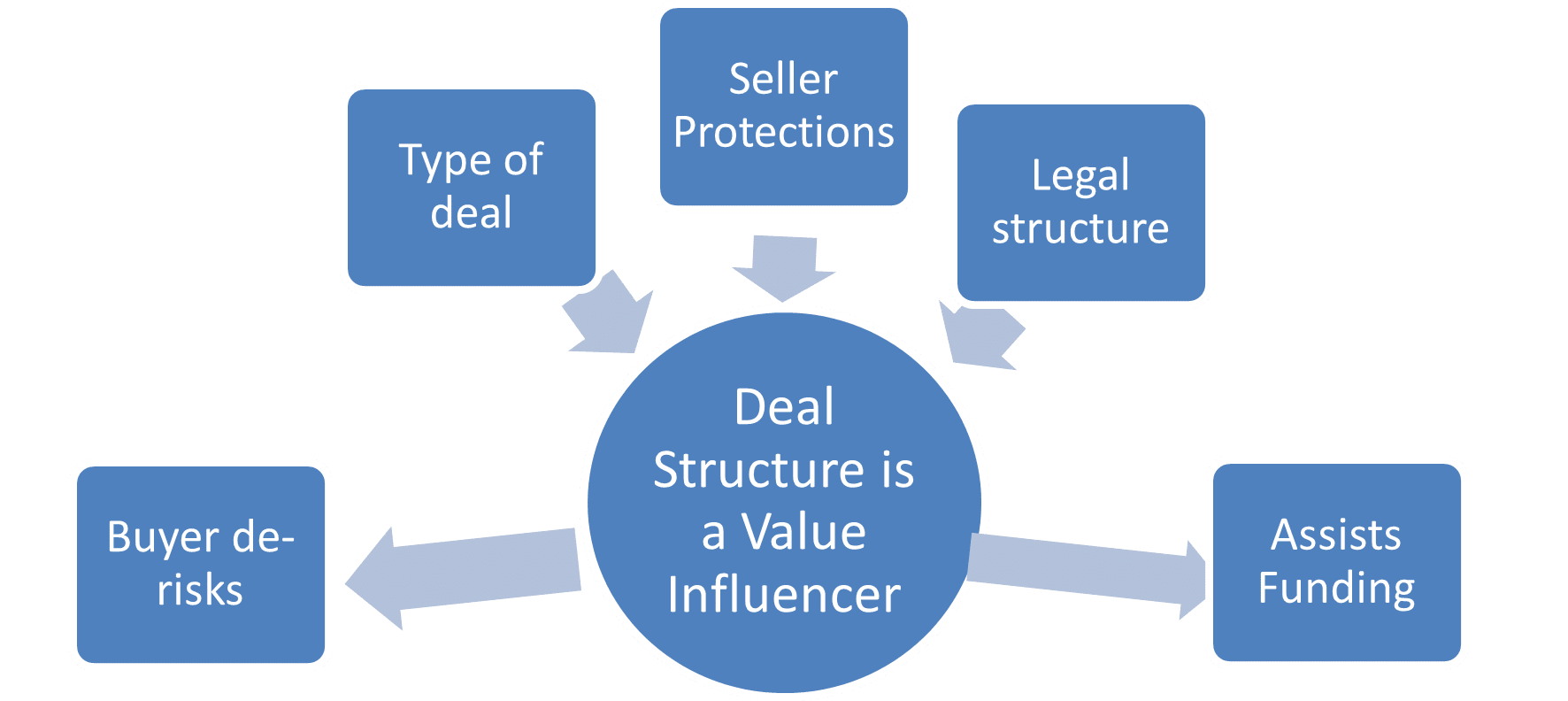

There are still some business sales where the full consideration is paid on completion and in cash, particularly in situations where competition to acquire the company has been intense and the asset has been well prepared for an exit. However, in private company acquisitions, we are increasingly seeing ‘deferred or performance-related payment’ deal structures used to fund deals and de-risk a transaction for a buyer. The inherent risks in a company have a material effect on the valuation. The greater the risks, the lower the value, but buyers can defer payments to offset this. The ‘value of money’ in having less capital tied up in an acquisition on day one can increase the value to a buyer, especially if deferred or performance payments are interest-free. There are many different deal structures and here we will examine the most common.

Performance Related Payments (PRP), Earn-outs and Deferred Payments

In these acquisitions, an initial cash payment is made on completion, followed by later, secondary payments over an agreed period of time. The payments might be a deferred sum (vendor loan); performance-related payments (PRP) or an earn-out. The secondary payments may help:

- The buyer ‘hedge’ risks and finances the deal from future profits.

- The seller ‘maximise’ the deal by linking the payments to future expected growth.

- The buyer incentivise integration.

- Offset risks such as major customer concentrations, or dependence on key individuals.

Larger corporate sales are more often all cash or cash and shares. In the small and mid-tier markets, however, deal structures with secondary payments are common. For example:

| Item | Amount | Payable | Note |

| Initial payment | £3,000,000 | At completion |

For the purchase of 100% of the share capital of the business debt-free/cash-free. |

| Debt-Free / Cash-Free | £250,000 | At completion |

The net asset value is currently £700,000. Debt including bank loans, hire purchases and corporation tax will be offset against cash. Any cash above the debt will be added to the deal value. If this amount is forecast at £250,000, it will be subject to normalised working capital, ensuring that debtors and creditors will be in their normal average range. |

| Performance Payment

(Target) |

£500,000 (estimated) | 2 years | 8 equal quarterly payments will be made following completion. Each quarterly payment will be calculated as 12.5% of the gross profit achieved above an agreed target in each quarter immediately preceding each payment. The maximum quarterly sum will be an agreed amount. |

| Deferred

(vendor loan) |

£500,000 | 2 Years | 8 equal quarterly payments will be made, subject to the continued service of JOHN SMITH as Managing Director, package to be agreed. |

| Forecast Consideration | £4,250,000 | As debt-free/cash-free can only be an estimate at completion, there will be a true-up based on the completion accounts which may be adjusted against the quarterly payments positively or negatively. |

In this example, gross profit has been used as the basis for future payments. Actual profit can lead to contention over who controls profit after a sale. There is a ‘minimus’ which means payments are not made if performance declines materially and a ‘maximus’ in case the buyer outperforms. A deferred sum has been used to maintain the service of the sellers to reduce risk and improve the handover. Interest has been offered as payments are for a short duration. Secondary deferred sums are at higher risk than cash, so it is important to understand that they are not guaranteed. The seller will seek protections and guarantees to reduce the risk on any secondary payments – ideally for the duration of the payments that:

- The business will be run materially the same as present and the buyer cannot compete with the seller.

- The sellers retain a seat on the board with good leaver/bad leaver clauses.

- The sellers have access to the company records and the issuing of payment statements.

- References, and cross guarantees from the buyer’s companies and debentures or even personal guarantees

- Interest on any late payment, and full payment due in the event of default and/or reversion of shares sold.

- Restrictive ‘non-compete’ covenants to no longer apply in the event of default.

- Shares may be held back and released as payments are made.

Loan Notes

A vendor loan may also be referred to as a loan note. The note is usually created by the vendor and therefore, the lender and will detail any interest and payment instalments. Institutional private equity uses loan notes regularly as part of their deal structure, often deferring any repayments until they achieve a later exit, normally 3-5 years. Using a vendor loan note defers the cost of capital enabling and thereby helping to fund the deal. Such deal structures normally offer sellers an attractive interest rate as an offset to the lack of loan instalments, especially where sellers have already received enough ‘beach’ money from any initial cash payment – beach money being enough to live quite comfortably, thank you. Normally earn-outs and deferred payments are subordinate to any bank borrowing and sellers should undertake reverse due diligence.

Elevator Deals

Elevator deals are for ambitious shareholder sellers as they go beyond earn-outs with secondary payments being made as growth is achieved. In these deal structures, sellers retain a proportion of shares after a buyout with the intention of a later sale at a materially ‘elevated’ value. This is often the preferred route of private equity buyers with both buyer and seller joining up to increase value by working together – typically over a 4-7-year period. Whilst this approach is a private equity favourite, trade and family offices also use this type of deal structure. By retaining shares in their business or by taking shares from the buyer, sellers have the potential to truly maximise, and ‘elevate’ the overall value.

This deal structure is well-suited for businesses with a strong track record of growth and promising future potential. Often, these arrangements combine elements of both a sale and an investment, where the transaction includes an injection of capital into the business to support its continued growth. The thinking behind this approach is that sellers can reduce their risk through the initial sale while retaining a percentage of ownership, which incentivises them to continue growing the business. If the company meets its agreed-upon growth targets, this retained stake can result in a significant upside. Typically, such deal structures involve a loss of control, as they usually require selling more than 50% of the business.

Buyers benefit by investing early at a cheaper price and potentially locking competitors out of an opportunity whilst usually still retaining the key people which increases the opportunity for growth and de-risks the proposition. They may also secure some economies of scale and reduce the seller’s requirement to concentrate on management thereby enabling them to focus on growth. Many of the protections for elevator deals are the same as for earn-outs and a quality shareholder’s agreement will be crucial in such a deal structure.

Shares (and paper for paper)

We have already seen in elevator deals how some buyers and sellers will actively offer and accept shares in some transactions. The premise is that it creates a mutual future journey with the underlying belief that equity may have more value than cash or debt even though it is at risk. In elevator deals, the shares are usually in a ‘rollover’ form – that means reinvesting some of the funds from the sale of mature shares into a new issue of the same or similar. However, some transactions may be on a ‘paper for paper basis’, the saying, of course, relating to paper share certificates. Minority shareholdings of less than 50% are at greater risk as they may come with little say in how a company is run and can even be diluted but a well-drafted shareholder’s agreement can provide some protections. Being offered shares as part of a deal is flattering, but a material investigation of what the shares are, and their likely value is important.

Preference Shares

Preference shares are used in some deal structures, particularly where an investment is being made to a company as well as a buy-out. Preference shares rank ahead of ordinary shares in terms of the company’s capital structure and dividends but have limited voting rights – the terms of the preference shares will be set out in the company’s articles of association. Typically, preference shares are fixed income ‘passive’ shares, similar to debt but secured by way of the shares and the preference or the priority that is given to them. Unlike ordinary shares, they are not linked to the success of the company and are usually cumulative, which means that if the holders are not paid their dividend in any period, then they will be paid in full when the company is subsequently able to. However, as with any shareholding, if the company becomes bankrupt, no money is paid.

Retentions

Retentions are also a form of deferred payment. The idea is that the purchaser pays all the money on completion but retains a proportion, ideally in an escrow account held by the vendor’s solicitors, in lieu of certain events. This is usually used as a holding mechanism against any adjustments to the completion accounts – it may be just whilst the final net asset value of a company is calculated at completion, or instead of a contract being renewed. Retentions work well because sellers can see their money and buyers have a straightforward means of clawing back in certain pre-defined eventualities if they need it.

Completion mechanisms

Most private company transactions will have a completion mechanism. Rarely will a price be agreed for the shares without reference to the balance sheet. The methods employed may vary but they may include:

Debt-free/cash-free – This is a method of agreeing to the ‘free’ cash in the transaction that is available and may therefore be added to the enterprise value. This will be subject to sufficient working capital being left in the business.

Locked box mechanism – Here, the equity price is calculated based on a defined historical balance sheet date agreed by the parties — the “locked box date” — and this price does not change, although there may be some leakage provisions. Any risk or reward from the lock box date, usually only a few months before completion, is at the buyer’s risk. Locked boxes are common in private share sale auctions as they enable direct comparison between bids.

Accounts finalisation – The accounts at completion will only be estimated as companies move to day-to-day trading. There are usually provisions in a transaction that the actual accounts will be produced within, for example, 3 months of a sale, and provisions that the estimated completion sum will have a ‘true-up’ against the actual finalised accounts and the price adjusted accordingly. The accounting policies in completion accounts will usually be defined as historic practices.

Conclusion

For some buyers, certain companies will influence their strategy so materially they will have a ‘we need, we want’ motivation which enables them to look at greater cash elements and higher valuations. Structured deals need careful advice and thought on both sides. If you would like more information about our service offering and case studies on our recent deals, please visit our website at https://avondale.co.uk. Alternatively, if you would be interested in a free consultation with one of Avondale’s experienced M&A advisors, please call us at +44 (0)1737 240888, email us at av@avondale.co.uk or fill out the attached form and we will get in touch straight away.